It is notoriously difficult to talk about the soul. If we believe that we have a soul, we tend to picture it vaguely – as some essence of ourselves, some core of our being which constitutes our ‘real’ selves or our ‘higher selves’. Even if we are not specifically religious we can all still resonate with the notion that there is some part of us which should not be sold, betrayed or lost at any cost. We can understand the idea that we can ‘lose our souls’ and still go on living, just as we can lose our lives but retain our souls. We still use the word ‘soul’ to mean something real or authentic. Whenever music, dance, architecture, food is said to have a soul, we mean that it is the real thing, that it speaks to the deepest part of ourselves. It is not a tangible reality, of course, but it is understood to be more real than ordinary life. So the first attribute of soul is as a symbol of depth and authenticity. Wherever it slips in, it stirs in us a sense that there is more to this world than meets the eye, something behind mundane events that is more than human. It stirs, in other words, a religious feeling, regardless of any religious denomination.

It is notoriously difficult to talk about the soul. If we believe that we have a soul, we tend to picture it vaguely – as some essence of ourselves, some core of our being which constitutes our ‘real’ selves or our ‘higher selves’. Even if we are not specifically religious we can all still resonate with the notion that there is some part of us which should not be sold, betrayed or lost at any cost. We can understand the idea that we can ‘lose our souls’ and still go on living, just as we can lose our lives but retain our souls. We still use the word ‘soul’ to mean something real or authentic. Whenever music, dance, architecture, food is said to have a soul, we mean that it is the real thing, that it speaks to the deepest part of ourselves. It is not a tangible reality, of course, but it is understood to be more real than ordinary life. So the first attribute of soul is as a symbol of depth and authenticity. Wherever it slips in, it stirs in us a sense that there is more to this world than meets the eye, something behind mundane events that is more than human. It stirs, in other words, a religious feeling, regardless of any religious denomination.

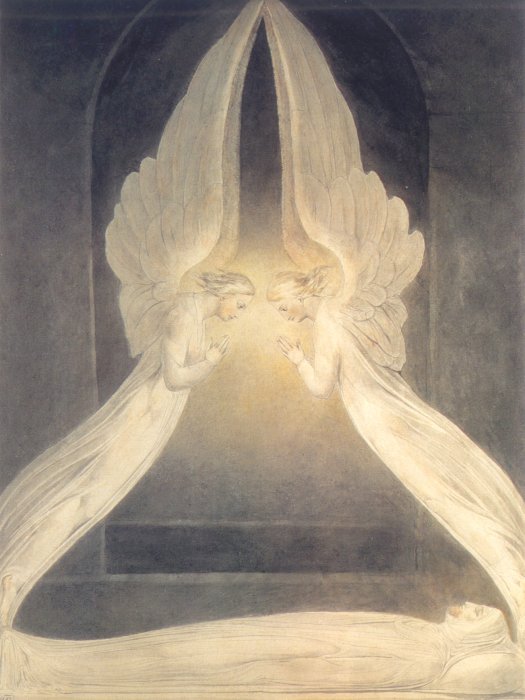

The notion of the soul is also oriented towards death. If we believe that some part of ourselves lives on after death, that part is the soul. Despite what modern materialists tell us – that we are only our bodies – we persist in feeling that we do in fact inhabit our bodies. We persist in feeling that the most real moments of our lives occur when we – perhaps our souls – temporarily leave our bodies, whether in joyful or in agonized passion. For example, we are ‘outside’ of ourselves when we are deeply engaged with a landscape or a lover, when we are ‘lost’ in a piece of music or dance. Conversely, when we are in heightened states of rage or fear, we spontaneously say: ‘I wasn’t myself!’, ‘I was beside myself!’, ‘I was out of my head!’ The Greek root of the word ‘ecstasy’ means to ‘stand outside (oneself)’. Such feelings enable us to experience the reality of what most, if not all, cultures have always asserted: that when we step outside of ourselves for the last time, at death, the body rots – but this essential, detachable part of ourselves, our soul, goes on.

While the soul is obviously connected with our sense of depth, of religion and of death, it is also connected with our sense of life’s purpose. ‘Where am I? Who am I? How did I come to be here… ?’ asked the philosopher and ‘father of existentialism’ Soren Kierkegaard. ‘How did I come into the world? Why was I not consulted? …. And if I am compelled to take part in it, where is the manager? I would like to see him.’ There are times when we have all echoed Kierkegaard’s indignation with our own questions to the manager – ‘What is my purpose in life? What am I for? Where do I go when I die?

Whoever is lucky enough to have found their purpose on Earth knows that they have done so because they feel fulfilled. They may have found their purpose in some job or in some person – a ‘soul-mate’ – but they are convinced that it is ‘meant’. Their lives are not necessarily free of suffering, but they are full of meaning. Those of us who are not so lucky nevertheless feel that we should search for a purpose, as if for our own souls. It might be that the search itself is our purpose.

The poet John Keats considered such questions too, suggesting that although people have ‘sparks of divinity’ in them, they are not ‘souls’ till they acquire identity – ‘till each one is personally itself’. Call the world if you please ‘The vale of Soul-making,’ he wrote in a letter to his siblings. ‘Then you will find out the use of the world.’ The question of our paradoxical condition – that we are born with souls yet also in another sense, have to make them – is at the centre of this book about the soul, its nature and destiny.

This book is therefore for people who are wondering what we consist of – what our essential nature is – and what happens to us when we die. It is for people who are sceptical of materialistic claims that we consist only of our bodies; sceptical of rationalist claims that the only reality is one that is subject to narrow empirical definitions. It is also for people who are disenchanted with the major religions – and especially Christianity – for squabbling over liturgy, gender issues and so forth, and neglecting the one thing religion is founded on: knowledge of the individual soul and its relationship with God. It is for people whose supernatural longing leads them to the East – to Buddhism and Taoism, for instance – only to be downcast by the difficulty of entering wholeheartedly into an alien culture and language. It is a book, too, for people who are drawn to New Age-style ‘spirituality’, only to find that this at best abstract and diffuse, at worst, woolly and embarrassing. In short, our souls long for meaning and belief just as much as they ever have, yet they can find no lasting nourishment in modern offerings of philosophy and science. We are like starving people who are given cookbooks instead of food.

Fortunately, help and sustenance lie to hand – not from some outlandish belief system or foreign land, but from a secret tradition within our own culture. It is a kind of ‘perennial philosophy’ which remains true no matter how radically times appear to change. Why then do we not all embrace it today? Because it is difficult and demanding. However, it is not difficult because it is, for example, in German or in academic jargon. It is difficult because it is subtle and elusive, more an imaginative vision of how things are than a system of though. Neither is it demanding because it requires tremendous effort, willpower and work; it is demanding because it wants us to turn our whole world-view upside down, forbidding us to fall back on the ideologies, whether of religious dogma or scientistic literalism, that we use simplistically to try to settle the matter of reality once and for all.

Instead, we are talking about a tradition of thinking or, better, seeing, which asks us to see through our own suppositions about the world, to dissolve our certainties, to read many levels into the world as if it were a great poem, and, in changing our perception, to transform our lives.

Although this tradition is secret, coursing through Western culture like an underground stream for the last eighteen hundred years, it occasionally wells up into the mainstream at times of crisis and transition – times, in fact, like our own. I have documented the extraordinary and fertility-bearing floods with inaugurated those great flowerings of culture amongst the Renaissance magi, the Romantic poets and the depth psychologists in my book The Philosopher’s Secret Fire. Now I want to describe the personal implications of this secret tradition for us as individuals. More, I want to initiate the reader into this brilliant and creative world-view in a language no longer alchemical and arcane but as straightforward as possible. For we all have to rediscover the ancient truths and retell the old myths in a way that speaks to our own generation.

Although its shape constantly changes to suit the age, the central tenets of the secret tradition remain the same. The idea, for example, that psyche, soul, constitutes the very fabric of reality; that humans are individual manifestations of a collective Soul of the World which interconnects all things; that imagination, not reason, is the chief faculty of the soul – though not the pale imitation of imagination as we now know it; that there is another world whence the soul comes at birth and to which it returns at death; and that the idea of gnosis, of a personal and transforming experience of divinity, is of the essence.

These are the sorts of notions I hope to unpack in the course of this book. Today they add up to world-view very different from the one in which we in twenty-first-century Western culture are accustomed. It is a sacred outlook, so to speak, which is rich in meaning by neither dogmatic nor agnostic. Nor is it against other systems of thought, such as science’s assumptions and to relate its hypotheses back to their mythic origins. Nor is it against religion. It merely enables us to dissolve the sclerotic ideologies which have hardened the heart of religion, letting it beat again. It particularly does not require new-fangled ideas or jargon, but tries to apply new insight to old ideas in order to present them afresh.

To this end, I begin with a survey of the way the soul is understood in tribal cultures very different from ours. I contrast their ideas with the sophisticated notion of soul developed by the Greek founders of our culture, and especially its apotheosis among Neoplatonists. They best expounded the traditional view that soul is the flagstone of reality, underlying both us and the world, and forming a bond between the two which modern dualism has mistakenly severed. By re-introducing soul to the world we re-enchant the environment and reconnect with our own experiences of the divine which we have been encouraged to ignore or forget, just as Western culture has suffered a collective loss of memory concerning itself.

I also re-introduce the soul’s traditional spokesman – that guide, guardian angel, Muse or daimon of which Soctrates spoke so eloquently – and show how it transforms chance to fate, and fate to a Providence in which whatever randomly occurs is seen to have been forever ordained.

I describe the strengths of our historically recent and culturally unique consciousness, centred on an indomitable ego – and also its weaknesses, not least our own fond belief that it is the highest form of consciousness there is. Central to this deconstruction is the role of initiation in dismantling our tendency to be over-conscious, over-rational – and over-literal. And I shall stress the necessity of reviving those rites of initiation which, though lost to us, are still informally and unconsciously enacted, especially by teenagers, in a desperate bid to keep us in touch with our soul, our authentic selves and the world at large.

Lastly, I describe what happens to the soul when it leaves the body, both during life and after death. Part of the impetus behind this book was provided by an eminent English novelist who, in reviewing Everyman by the renowned US novelist Philip Roth, praised Roth’s view of death as an exchange of ‘our fullness for that endless nothing.’ He further congratulated Roth on ‘casting such a cold crystalline eye on the unfairness of death, and concluding that there are no answers: just the terror of nothingness that we all share.’ But, on the contrary, we do not all share such an impoverished view, and as exponents of imagination these novelists should know this – and know better.

Anyone with even a modicum of initiatory experience knows that death is a portal into that greater reality which can already be glimpsed in this world as an imaginative experience of the Otherworld. Whatever physical pain members of traditional cultures may suffer, they do not suffer the mental anguish of eminent modern novelists because they know that they will pass seamlessly into an afterlife where, gathered up by rejoicing ancestor, they will live forever in an ideal version of their beloved homeland, free of sickness and want. Many, perhaps most, people in Western culture – particularly those who are uncontaminated by scientistic and existential nihilism – believe much the same thing. As the Greeks maintained, death is not the opposite of life but of birth – life is a continuous realm out of which we are born; which (as Plato says) we can dimly remember during our existence; and to which we return when we die – return to that totality of life compared to which mortal existence seems but a dream-like fragment.

At the same time, there is no doubt that Afterlife can appear at worst, as hellish and, at best, as a Hades-like realm of shades which, according to old Irish laments for example, are pale by comparison with the richness and colour of l

ife in this world. The Afterlife is paradoxical, in other words; and I shall explain how it tends to mirror ourown souls so that we get the Afterlife we deserve – the Afterlife we already, in a sense, inhabit without being aware of it.

It is a purely modern affectation to claim that we can know nothing of life after death. It means ignoring the accounts of mystics, poets, mediums, medicine-men, shamans, prophets and so-called Near-Death Experiencers, to say nothing of those who have crossed the narrow sword-bridge during moments of love or rapture, during heightened states of illness or drug taking, in visions or dreams. Such experiences may last only moments, but they can outweigh in importance years of mundane existence. ‘Strange as it may seem,’ wrote the most famous of al humanists, Erasmus, in 1519, ‘there are even men among us who think, like Epicurus, that the soul dies with the body. Mankind are great fools, and will believe anything.’

Extracted from A Complete Guide to the Soul by Patrick Harpur, available from Cygnus.